Study shows children and birds learn alike

Your child is your pride and joy — and why not, every parent should be a proud one, even if your child might be bird brained. Or maybe birds are baby brained? In any case, a new study has found that pigeons can categorize and name both natural and manmade objects–and not just a few objects. These birds categorized 128 photographs into 16 categories, and they did so simultaneously.

The more scientists study pigeons, the more they learn how their brains–no bigger than the tip of an index finger–operate in ways not so different from our own. The finding suggests a similarity between how pigeons learn the equivalent of words and the way children do.

“Unlike prior attempts to teach words to primates, dogs, and parrots, we used neither elaborate shaping methods nor social cues,” Ed Wasserman corresponding author of the study says of the study.

“And our pigeons were trained on all 16 categories simultaneously, a much closer analog of how children learn words and categories.”

For researchers who have been studying animal intelligence for decades, this latest experiment is further proof that animals — whether primates, birds, or dogs — are smarter than once presumed and have more to teach scientists.

“It is certainly no simple task to investigate animal cognition; But, as our methods have improved, so too have our understanding and appreciation of animal intelligence,” he says.

“Differences between humans and animals must indeed exist: many are already known. But, they may be outnumbered by similarities. Our research on categorization in pigeons suggests that those similarities may even extend to how children learn words.”

The pigeon experiment comes from a project published in 1988 and featured in The New York Times in which researchers discovered pigeons could distinguish among four categories of objects.

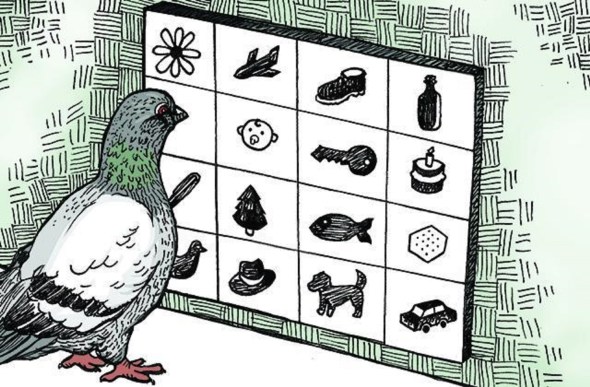

This time, the researchers used a computerized version of the “name game” in which three pigeons were shown 128 black-and-white photos of objects from 16 basic categories: baby, bottle, cake, car, cracker, dog, duck, fish, flower, hat, key, pen, phone, plan, shoe, tree. They then had to peck on one of two different symbols: the correct one for that photo and an incorrect one that was randomly chosen from one of the remaining 15 categories. The pigeons not only succeeded in learning the task, but they reliably transferred the learning to four new photos from each of the 16 categories.

Pigeons have long been known to be smarter than your average bird–or many other animals, for that matter. Among their many talents, pigeons have a “homing instinct” that helps them find their way home from hundreds of miles away, even when blindfolded. They have better eyesight than humans and have been trained by the U. S. Coast Guard to spot orange life jackets of people lost at sea. They carried messages for the U.S. Army during World Wars I and II, saving lives and providing vital strategic information.

Researchers say their expanded experiment represents the first purely associative animal model that captures an essential ingredient of word learning–the many-to-many mapping between stimuli and responses.

“Ours is a computerized task that can be provided to any animal, it doesn’t have to be pigeons,” says Psychologist Bob McMurray, another author of the study.

“These methods can be used with any type of animal that can interact with a computer screen.”

The research shows the mechanisms by which children learn words might not be unique to humans.

“Children are confronted with an immense task of learning thousands of words without a lot of background knowledge to go on,” he says.

“For a long time, people thought that such learning is special to humans. What this research shows is that the mechanisms by which children solve this huge problem may be mechanisms that are shared with many species.”

Of course, the recent pigeon study is not a direct analogue of word learning in children and more work needs to be done. Nonetheless, the model used in the study could lead to a better understanding of the associative principles involved in children’s word learning.

“That’s the parallel that we’re pursuing,” he says, “but a single project–however innovative it may be–will not suffice to answer such a provocative question.”

It may seem a stretch, but it is research like this that will help us further understand how our brain operates. It may also offer insight into better ways to teach children more effectively in the not too distant future.

Sources:

Wasserman, E., Brooks, D., & McMurray, B. (2015). Pigeons acquire multiple categories in parallel via associative learning: A parallel to human word learning? Cognition, 136, 99-122 DOI: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.11.020

I wonder how any other animals learn in the same way as these pigeons and humans do. I have seen tests like this performed on apes/monkeys with some success, and although I understand that humans are not the only ones who have the ability to learn in such a way, it still amazes me every time. How long did it take the pigeons to pick up the words and categories? Or what is the difference in time between these birds and humans learning the same words? I believe it would be interesting to see how many more words and categories that the pigeons would be able to learn. With pigeons being a bird that is already known for being smart, I wonder how other birds would do in a test like this.

LikeLike

February 15, 2015 at 7:38 pm

Testing other birds would be interesting, it would also be interesting to see the differences in brain structure amongst the birds themselves.

As far as how fast they learned compared to humans, I didn’t see a specific reference to it in the study (I may have missed it admittedly), however I think it was fairly comparable.

I agree testing how many different categories and words we could teach a bird would be an awesome follow up study. Thank you for such a well thought out comment!

LikeLike

February 16, 2015 at 4:30 pm